Dear Reader,

Today’s letter is a big one. It is a story I have been sitting on for months. It is also the start of a new column where I will be writing specifically about my experiences as a photographer, or rather, a person living and trying to make art. If you are a free subscriber you will eventually run into a paywall. I have a desire to keep this story as accessible to as many people as possible, and the images and words I’ve shared are deeply personal. Some content has been saved for paid subscribers. If this work is meaningful to you and you would like to continue receiving this specific column, I invite you to become a paid subscriber for $5/mo. Thank you for reading!

“You can do it like it’s a great weight on you, or you can do it like it’s a part of the dance” - Ram Dass

On an early Tuesday morning back in August, with a freshly downloaded playlist blaring and air-pods shoved as far in towards my eardrums as physically possible, I let out a giant sigh of relief and stared blankly out the window.

I had just run what felt like a quarter of a mile from the parking lot all the way to the platform with my luggage and camera equipment in order to not miss my train. Now safe in my assigned seat for the next several hours, I whipped out my phone, opened the notes app, and began to write.

“My inner compass and filters I use to help me decipher how much to share in the digital space aren’t quite working like they used to...I have to try and protect my future self while things still feel fuzzy in my mind…I think there will be a time when I feel less disoriented and overwhelmed. I also know that the pressure I feel right now to solve everything so I can show up more fully to the things that bring me life, is for the most part, self-imposed. No one is actually demanding I be anything other than who I am at this moment! Alas, the distortion that depression can cause often says otherwise.”

I have struggled to write this letter about my trip to see Anna and the pictures we made together because, in many ways, the past several weeks have been flooded with similar thoughts. I have felt ashamed and discouraged circling back to a state of mind that I thought I'd permanently escaped since that moment on the train — a kind of existential malaise that this project originally helped catapult me out of.

I have never wanted to put pressure on photography to save me or pull me out of a grief spiral because when I do, it makes things worse. And although at times it does function as a respite, making pictures is my job, which means that whether I am sad or not, I still have to show up. Like any vocation that demands our bodily presence, this means I’ve often had to compartmentalize my feelings or state of mind, even as I am walking into a space that demands I be entirely tapped into both. I don’t know how I do it (or how any of us do it) but when I have to, I inevitably find a way.

When I got on the train that day, I was in the midst of what I now recognize as the tail end of a mental health crisis. I had just admitted to both my best friend and my therapist about the incessant suicidal ideations that had been plaguing me for weeks. I was just starting to acknowledge the depths of a season of depression I hadn’t realized I was in. The questions running through my mind had nothing to do with whether or not my life was worth living, but whether or not I had the actual capacity to live it.

I felt burnt out, utterly exhausted, and completely detached from the world around me. Admitting this out loud was one of the most terrifying things I’ve ever had to do, but a move I had to make if I was serious about preventing things from getting worse. My therapist and I had begun talking about the possibility of SSRIs, an option that was quickly tabled the moment I received an official diagnosis of ADHD. The game plan was to try out medication for the recent development and wait to see how I felt.

I felt stupid. Weak. Embarrassed by my lack of desire to keep trying. But the diagnosis did provide an avenue of possibilities for what to do next. I did not tell my family about my ideations, and I did not feel it was appropriate to write about it in real-time, though I did vaguely address it in this essay I wrote about my diagnosis. Instead, my mental state became a secret I held in the back of my mind as I left the city to go see Anna.

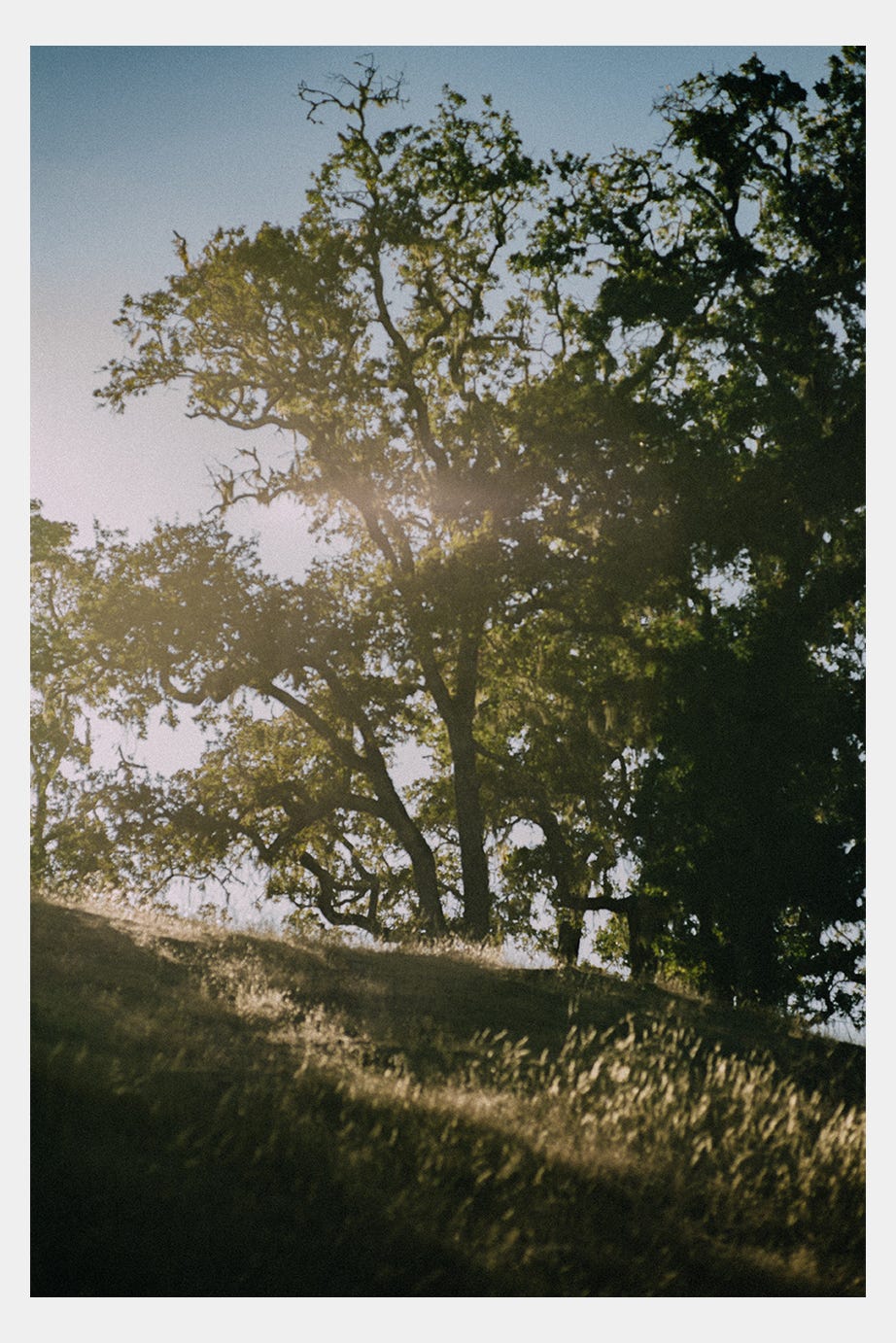

Walking around the ranch, I felt I had been given a temporary save — an escape from the pressure to figure things out and figure them out quickly. Getting to leave LA at that moment felt like a true miracle, and I also knew the clock was ticking. My time away was limited and everything would be waiting for me when I returned. Still, I saw the retreat as a grace.

I did not care about the money I was being paid to make the photographs—I would have honestly paid someone to let me make them. I was equally thrilled about the opportunity to meet and photograph Anna, as I was to temporarily mute my woes. At the ranch, nothing mattered to me except being present to the moment and the real assignment I had been given: make pictures of Anna— and make them fucking good.

I’ve retraced my steps in an attempt to tell this story correctly. I’ve sifted through the pictures in order to remember how I felt while making them so that I could write about it. But my memories are shrouded by the state of my mental health at the time—it has been difficult for me to see beyond it. I keep wondering, How the hell did I do that? How was I able to make all of this, while feeling all of that?

My questions have reconnected me to the awe and wonder of art-making, and right now I can’t help but feel immense gratitude for the magic of it. My reflections have increased the faith I have in myself. They remind me that I can make beautiful things, even when I’m in pain.

When I told Anna how much I was struggling to write this, she urged me to write about what was on my heart now. I was reminded of a question a friend of mine often asks in place of “How are you?” which is “What is alive for you in this moment?”

Anna also suggested I speak my thoughts out loud into a voice memo and then play it back to see where the story might be. I took her advice and ended up rambling to myself for over an hour. When I played it back on a long walk the next day, I felt a mixture of dread and heartbreak as I listened to a voice that was so clearly filled with inner conflict and discouragement: “…I do not feel open-hearted.”

Weeks have passed and I’ve scraped my way further to the bottom of the barrel. What am I avoiding? What is the feeling I don’t want to admit? Beyond a lack of open-heartedness, I have not wanted to admit that recently, my mind had been consumed by feelings similar to the ones that visited me last summer, exhaustion, and despair.

I'm confused because, in so many ways, things have been infinitely better since then. When I returned from my three-day trip up the Central Coast I started the medication for my ADHD and noticed an immediate shift. I felt a sense of hope that came simply from something being done even if the future was uncertain.

Not long after, I met someone, fell in love, and experienced a profoundly beautiful relationship that grew and challenged me beyond what I thought was possible. This person also had ADHD and years of experience in managing it. Beyond seeing the beauty of my queerness being reflected back to me, I witnessed the profound gift of being neurodivergent in the context of romantic love and a blossoming friendship which made me feel safe. I felt the freedom to practice showing up as my full self.

When things ended abruptly with J., I promised myself I would not get depressed. I would not allow the shock of abandonment to close my heart. I would recover quickly and move on as fast as I could. Even as I made these promises to myself, I knew there was very little I could do to speed up the natural grief process. I knew I'd be forced to face the raw elements of myself that had been temporarily soothed by the pleasures of falling in love.

One of the most difficult aspects of loss is returning to all that remains and seeing it as enough. Knowing that I am enough, that my life is enough with or without this person, has been my daily practice. But knowledge does not erase the exhaustion that comes from the reality of being alone. I know that a partner can't solve it all, but I also know the relief that comes from sharing a life or your burdens with another in an intimate relationship. A wonderful relief; love heals. I crave and desire partnership. I dream of building a life with someone—I’m not afraid to admit that. To come close to that in some small way, and then lose it, will never not be painful.

After the breakup, I first indulged in feeling “back to square one." But then I recalled the awareness of a truth that has since comforted me: I have never been here before. I am not who I was eight months ago. I am not even who I was one month ago.

Since that day on the train, I have grown, shed, and evolved. I have acquired new tools, both spiritually and physically. I am no longer a stranger to the ideations that appear in moments of sheer exhaustion—I am learning to not mistake them for the truth. I see most of the despair that creeps in as an alarm for much-needed rest. And even if I can’t always access that rest physically, I know that it is imperative that I find a way to slow down, drop in, and ask my heart, “What is alive for you in this moment?”

I think it has felt nearly impossible to write about what it was like to make pictures of Anna because that moment in time feels so deeply sacred to me. I thought it would be fun and cool to write a tell-all of the inner workings of my mind while collaborating on this project with her, but when I try to go there, my mind goes blank.

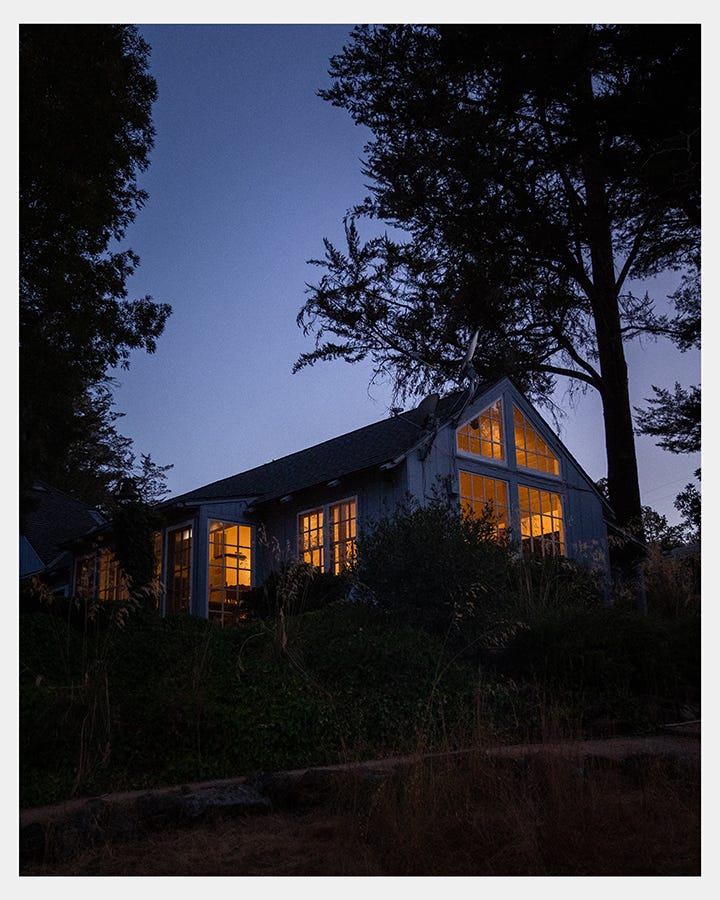

I do remember feeling seen, cared for, and acknowledged by Anna. Both our care, nervousness, and dedication to the work were glaringly obvious the moment we met. After grocery shopping for sustenance, Anna drove us deeper into the hills towards the ranch. To this day, I could not tell you where we were— I was too consumed by conversation and coming to grips with the fact that I was sitting in Anna Fusco’s van. There was an assumption between us that we would talk about a lot of things during our time together that we never actually got around to talking about. We both thought it would go differently than it did, yet of course I now can't imagine it going any other way than how it did.

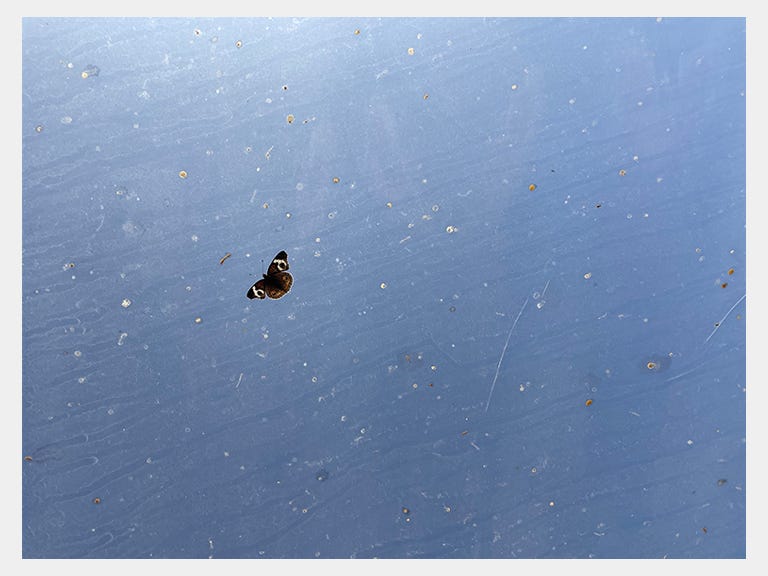

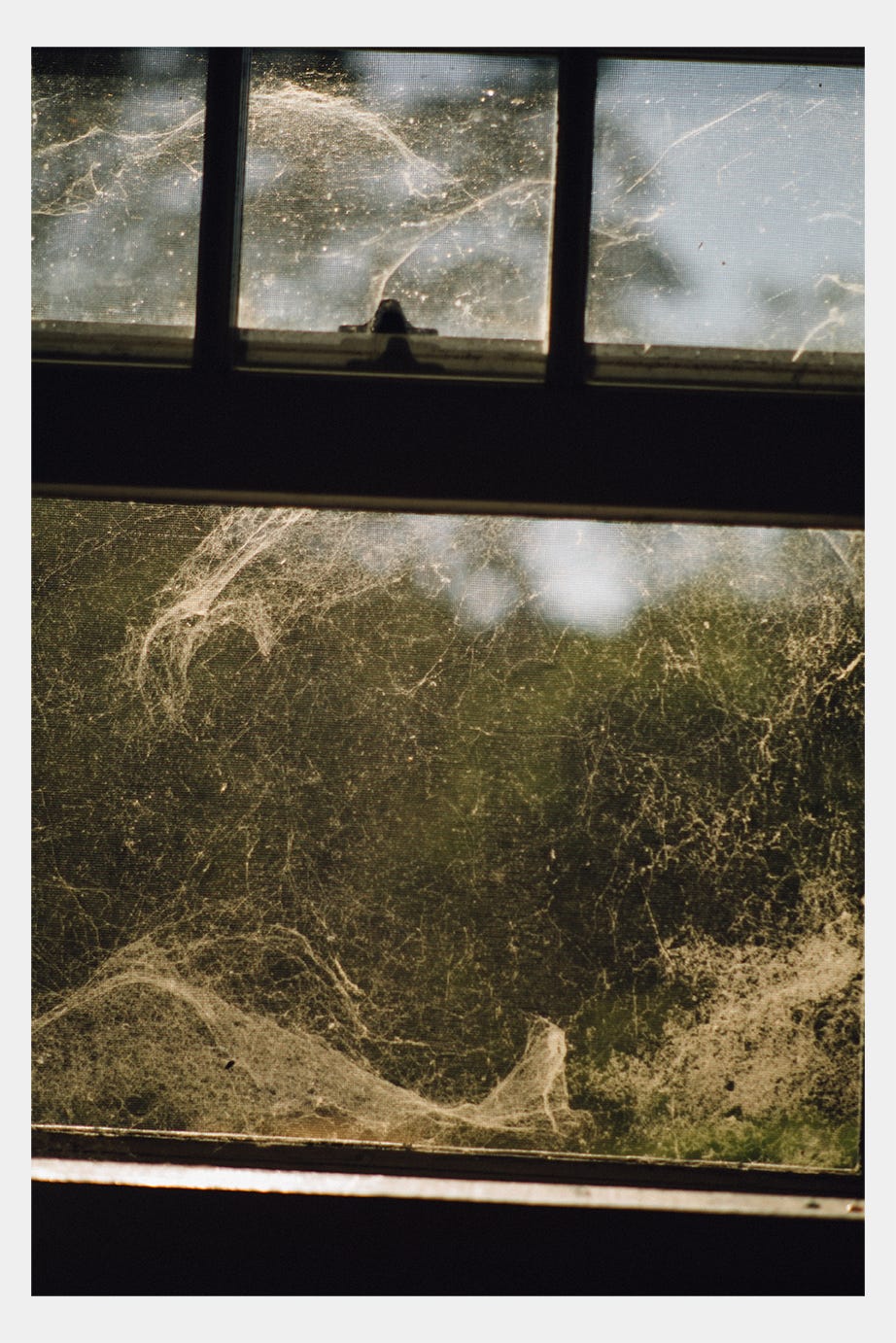

For the most part, we were entirely focused on the pictures themselves. Despite the fact that they were personal (Anna was literally walking around in underwear and half-naked for almost two days), there was also the sense that the pictures were outside of ourselves. We stood side by side, staring at a rock, a flower, a dilapidated barn, and asked one another repeatedly: How do we want to do this? The line between subject and photographer was increasingly blurred as the hours passed. At one point, while hunched down on my knees staring straight into the sun and Anna towering over me next to the dog, she looked at me dead in the eye and said “Joy, you’re working so hard.

The comment knocked me out of my state of hyper-focus and I suddenly felt my body again, my feet sweating in my green crocs, my white overalls stretched tightly across my bent knees, and my back aching. I wanted to break down in tears right then and there. Instead, I think I let out a little laugh mixed with an exhale and said Thank you.

I saw a lot of Anna that day. I saw her shift from clinging tightly to an idea of how she thought things ought to be, to a continual surrender when she’d suddenly remember that things are often better when you let go and let god.